Beyond Brancusi, the Space of Sculpture

By Eveline Morel | December 17th, 2013 | Category: L.A. Art & Culture | Comments Off on Beyond Brancusi, the Space of Sculpture“They are imbeciles who call my work abstract; that which they call abstract is the most realistic, because what is real is not the exterior form but the idea, the essence of things.” —Constantin Brancusi

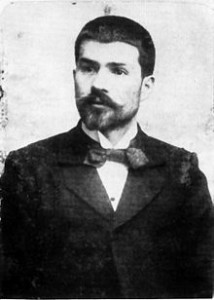

Constantin Brancusi, is often regarded as one of the most important sculptors of the 20th Century and one of the greatest founders of modern abstract sculpture. Born in a small Romanian village in 1876, he left home at the age of eleven, but his village roots have continued to influence his work in Paris. His work took myths, folklore, primitive cultures, and traditional old-world sources as inspiration and pared them down to their essence into simple, abstract shapes and forms.

Constantin Brancusi, is often regarded as one of the most important sculptors of the 20th Century and one of the greatest founders of modern abstract sculpture. Born in a small Romanian village in 1876, he left home at the age of eleven, but his village roots have continued to influence his work in Paris. His work took myths, folklore, primitive cultures, and traditional old-world sources as inspiration and pared them down to their essence into simple, abstract shapes and forms.

Brancusi worked directly with the materials—primarily stone, marble, bronze, wood, and metal—pioneering the technique of direct carving, rather than working with intermediaries (plaster or clay models). He would meticulously polish pieces to achieve a gleam that suggested infinite continuity into the surrounding space, which was reflected back on the sculpture.

His work was not meant to represent reality, but to capture that fleeting sense of movement, in a way, to capture the soul. As he said about the Fish sculpture: “When you see a fish you don’t think of its scales, do you? You think of its speed, its floating, flashing body seen through the water . . . If I made fins and eyes and scales, I would arrest its movement, give a pattern or shape of reality. I want just the flash of its spirit.”

Three of his larger sculptures, still in Romania, close to his hometown, show the old-world influences as they blend symbolism with sleek, modern shapes in timeless pieces that leave the viewer to reflect upon reality, perfection, invariably looking inward, as one looks outward at the sculpture. Brancusi’s work was largely fueled by myths, folklore, and “primitive” cultures. These traditional, old-world sources of inspiration formed a unique contrast to the often sleek appearance of his works, resulting in a distinctive blend of modernity and timelessness.Although he professed not to use obscure formulas, Brancusi’s works often use symbols: “Don’t look for obscure formulas or mystery in my work. It is pure joy that I offer you. Look at my sculptures until you see them.”

Three of his larger sculptures, still in Romania, close to his hometown, show the old-world influences as they blend symbolism with sleek, modern shapes in timeless pieces that leave the viewer to reflect upon reality, perfection, invariably looking inward, as one looks outward at the sculpture. Brancusi’s work was largely fueled by myths, folklore, and “primitive” cultures. These traditional, old-world sources of inspiration formed a unique contrast to the often sleek appearance of his works, resulting in a distinctive blend of modernity and timelessness.Although he professed not to use obscure formulas, Brancusi’s works often use symbols: “Don’t look for obscure formulas or mystery in my work. It is pure joy that I offer you. Look at my sculptures until you see them.”

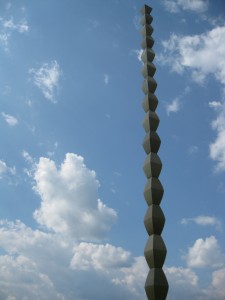

The Endless Column or Column of the Infinite, created out of 17 rhomboidal modules worked in metal, stretches out 96 feet high. The column, honoring the soldiers who had died in the First World War, stretches out into seeming endlessness as the viewer’s eyes search for the top of the column. The Table of Silence blends together familiar shapes and rites: the warriors sitting down to one last meal before battle, simple hourglass shapes of primitive stools. The distance of the seats away from the table and the heaviness of the stones impart a feeling of absence, the silence that exists in the absence of those who should be present upon the table.  The Gate of Kiss, sculpted out of travertine marble, featuring designs with two joined half-circles, is said to represent the transition to another life as one passes through it.

The Gate of Kiss, sculpted out of travertine marble, featuring designs with two joined half-circles, is said to represent the transition to another life as one passes through it.

Brancusi’s use of biomorphic forms and the way he integrates the sculpture with its base influenced the work of Isamu Noguchi. The way he embraced the materials’ distinctive qualities and his focus on the technique of direct carving influenced the work of Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Jacob Epstein, as well as the Minimalist movement of the 60s. The Norton Simon’s group exhibition “Beyond Brancusi: The Space of Sculpture,” organized by Associate Curator Leah Lehmbeck, uses Brancusi’s sculpture Bird in Space as anchor for the show, as it investigates Brancusi’s influence on the work of some of the great sculptors of the Twentieth Century: Henry Moore, Donald Judd, Robert Irwin, Larry Bell, Craig Kauffman, and Dan Flavin.

As one looks at Larry Bell’s cube, Henry Moore’s Reclining Form, and DeWain Valentine’s Large Wall, one is invariably led to reflect on the essence of shapes and forms, as best stated by Brancusi himself: “Simplicity is not an end in art, but we usually arrive at simplicity as we approach the true sense of things.”