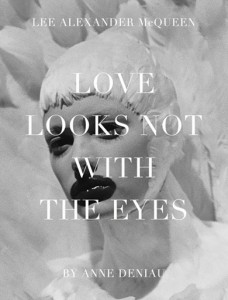

LOVE LOOKS NOT WITH THE EYES by Anne Deniau

By Arun Nevader | January 17th, 2013 | Category: Book Reviews, Non-Fiction | 1 Comment »

For starters, Alexander McQueen created ‘savage beauty’ in every way he chose for having taken couture beyond fashion to high art. We saw it for many years on the runway and then we saw it again collected at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2011. Pure talent let him push all our boundaries much harder than most artists could do. And he did. What we saw were his iconographic narratives, but what we loved were his breathtakingly beautiful art forms.

For starters, Alexander McQueen created ‘savage beauty’ in every way he chose for having taken couture beyond fashion to high art. We saw it for many years on the runway and then we saw it again collected at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2011. Pure talent let him push all our boundaries much harder than most artists could do. And he did. What we saw were his iconographic narratives, but what we loved were his breathtakingly beautiful art forms.

And so this is how Love Looks Not with the Eyes by Anne Deniau took shape, released in October 2012, more than two years after McQueen took his own life. Through hundreds of her exclusive backstage photographs shot over a 13-year period, Deniau captured a chronology narrative of McQueen’s visionary art as early journey, disarming discovery, and fleeting self-knowledge found in captured beauty—an evocative three-part collection of images spanning his career from when he emerged in 1992 to his death in early 2010. She divides her picture narrative into three chronological chapters, Egeria, Allegoria, and Elegia. The divisions mark the archetypal stages in artistic development, and give shape to his meteoric career.

Deniau’s photos are as arresting as her subject matter, where both photo and subject are layered and never one-dimensional. She taps into the meaning of McQueen’s arm tattoo, “Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind,” a line that he had body-inked from Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Her photos make us understand that for McQueen, beauty stood embodied, radiant and triumphant through a dreamscape of a material world often turned upside down, figured at once Gothic, dark, disembodied, disconnected, deceptive, terrifying and yes, thrilling.

Deniau’s photos are as arresting as her subject matter, where both photo and subject are layered and never one-dimensional. She taps into the meaning of McQueen’s arm tattoo, “Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind,” a line that he had body-inked from Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Her photos make us understand that for McQueen, beauty stood embodied, radiant and triumphant through a dreamscape of a material world often turned upside down, figured at once Gothic, dark, disembodied, disconnected, deceptive, terrifying and yes, thrilling.

Beauty for Lee Alexander McQueen was that impeccably tailored female form illuminated from within a theatrical dream space. The female model wore the dream’s symbolic conflation of forces in her singular beauty and construction. She appeared as part of the theater to resist the pull toward sequestered darkness and control. Her beauty made known that dreamy void, provoking us to react in thrilling astonishment, sometimes shocking fear. She emerged out of what is awesome and sublime—feelings grounded in our collective cultural fascination with many unknowns. This was nothing new—the space where beauty challenges the sublime, where art confronts what we fear the most. We were challenged not by a Gothic narrative frisson because it had been told and felt before. We were challenged by the perfect and imaginative craft of his couture, which kept us as his audience.

Beauty for Lee Alexander McQueen was that impeccably tailored female form illuminated from within a theatrical dream space. The female model wore the dream’s symbolic conflation of forces in her singular beauty and construction. She appeared as part of the theater to resist the pull toward sequestered darkness and control. Her beauty made known that dreamy void, provoking us to react in thrilling astonishment, sometimes shocking fear. She emerged out of what is awesome and sublime—feelings grounded in our collective cultural fascination with many unknowns. This was nothing new—the space where beauty challenges the sublime, where art confronts what we fear the most. We were challenged not by a Gothic narrative frisson because it had been told and felt before. We were challenged by the perfect and imaginative craft of his couture, which kept us as his audience.

Alexander McQueen knew what he loved without fear and with utter certainty. His models knew it, and they radiated it for him. His dreamscape world would last for 15 minutes, and then be reimagined every season, for years. The runway show began and ended quickly. If it seems all too common to think of beauty as brief and ephemeral, then so be it. McQueen, though, could find his material in the insubstantial stuff of black duck feathers, embroidered silk lace, and fresh flowers. He dared any material to overtake the perfection in his use of it.

Alexander McQueen knew what he loved without fear and with utter certainty. His models knew it, and they radiated it for him. His dreamscape world would last for 15 minutes, and then be reimagined every season, for years. The runway show began and ended quickly. If it seems all too common to think of beauty as brief and ephemeral, then so be it. McQueen, though, could find his material in the insubstantial stuff of black duck feathers, embroidered silk lace, and fresh flowers. He dared any material to overtake the perfection in his use of it.

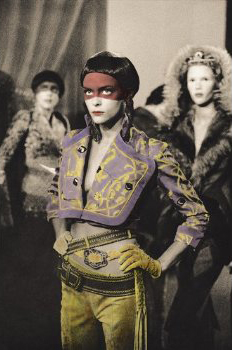

It did not end for Deniau when it seemed over in February of 2010—she had a photographic record of 13 years—her years of “backstages,” many of them with intimate candid shots of the designer at work. We’ve had all our McQueen runway dreams one at a time for years, but Deniau has given us his dream saga across time in a single volume of mostly stunning black and white film images, color here and there with less success, especially in skin tone and makeup. The power of each photograph is linked to many others, and not always by the quality of photographic technique. She has plenty of photographic technique, shooting primarily to see what is and is not there—the real payoff in backstage photography. Granted, it’s hard to miss with a subject like hers. But there’s a Proustian, hypnotic pleasure in the meticulous flow of one photograph into the next. She creates her intensely personal “remembrance of things past” in arranging 400 images. Deniau’s book feels like a still photo documentary, a meditation on a designer’s signature art through the art of her own image making.

It did not end for Deniau when it seemed over in February of 2010—she had a photographic record of 13 years—her years of “backstages,” many of them with intimate candid shots of the designer at work. We’ve had all our McQueen runway dreams one at a time for years, but Deniau has given us his dream saga across time in a single volume of mostly stunning black and white film images, color here and there with less success, especially in skin tone and makeup. The power of each photograph is linked to many others, and not always by the quality of photographic technique. She has plenty of photographic technique, shooting primarily to see what is and is not there—the real payoff in backstage photography. Granted, it’s hard to miss with a subject like hers. But there’s a Proustian, hypnotic pleasure in the meticulous flow of one photograph into the next. She creates her intensely personal “remembrance of things past” in arranging 400 images. Deniau’s book feels like a still photo documentary, a meditation on a designer’s signature art through the art of her own image making.

It’s best to view Love Looks Not with the Eyes though, as a defining artist’s chronicle and tribute more than as a book of photography. Fortunately, the book is really about Alexander McQueen. Deniau had the great fortune of knowing and working with the designer for years. Her black and white images carry the most power in the book. Images, like the ones we find from the Horn of Plenty show in March 2009 Paris, show us why. McQueen often used background darkness to give his models an otherworldly, emergent quality in how they were lit. We found ourselves drawn into the surrounding set darkness. Deniau often captures that instinct in us too, and we start recognizing the dual value in the seen and unseen before us. There’s irony, beauty, and fear in that when we think of the designer.

It’s best to view Love Looks Not with the Eyes though, as a defining artist’s chronicle and tribute more than as a book of photography. Fortunately, the book is really about Alexander McQueen. Deniau had the great fortune of knowing and working with the designer for years. Her black and white images carry the most power in the book. Images, like the ones we find from the Horn of Plenty show in March 2009 Paris, show us why. McQueen often used background darkness to give his models an otherworldly, emergent quality in how they were lit. We found ourselves drawn into the surrounding set darkness. Deniau often captures that instinct in us too, and we start recognizing the dual value in the seen and unseen before us. There’s irony, beauty, and fear in that when we think of the designer.

In photography, especially backstage where beauty and talent are always everywhere, we’re never quite sure if it’s the beauty or the photo that makes it great. Perhaps that’s the mark of a great backstage photograph—it’s like a waiter who delivers the goods, but never wants to be seen. The image remains transparent in some way that lets us focus on McQueen. So, none of the book’s images are titled, and we stay focused on what we are seeing. Anne Deniau will make the viewer stop and think about a photo, but it’s our fascination with Alexander McQueen’s art that keeps us turning the pages.

In photography, especially backstage where beauty and talent are always everywhere, we’re never quite sure if it’s the beauty or the photo that makes it great. Perhaps that’s the mark of a great backstage photograph—it’s like a waiter who delivers the goods, but never wants to be seen. The image remains transparent in some way that lets us focus on McQueen. So, none of the book’s images are titled, and we stay focused on what we are seeing. Anne Deniau will make the viewer stop and think about a photo, but it’s our fascination with Alexander McQueen’s art that keeps us turning the pages.

Love Looks Not with the Eyes

By Anne Deniau.

409 pp. Abrams.

Your article LOVE LOOKS NOT WITH THE EYES by Anne Deniau – Agenda Magazine write very well, thank you share!