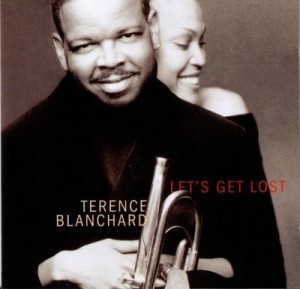

Terence Blanchard – Legendary Musician Talks About What Has Piqued His Interests All These Years

By Matthew Allen | May 31st, 2012 | Category: Indie Hotspot, iRock Jazz, Jazz, Music | Comments Off on Terence Blanchard – Legendary Musician Talks About What Has Piqued His Interests All These Years When examining the arc of one’s artistry, what must be considered above that individual’s personal aptitude of his respective skill is the fact that you are a product of your environment. Terence Blanchard is an arc type for this principle, extracting the rich spirit of his New Orleans upbringing from his trumpet onto everything he’s touched: from his teenage stint with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers to his stature as one of the most respected film composers of the last two decades.

When examining the arc of one’s artistry, what must be considered above that individual’s personal aptitude of his respective skill is the fact that you are a product of your environment. Terence Blanchard is an arc type for this principle, extracting the rich spirit of his New Orleans upbringing from his trumpet onto everything he’s touched: from his teenage stint with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers to his stature as one of the most respected film composers of the last two decades.

His signature emotive, long note solos from his 52 scores—including Eve’s Bayou and Love & Basketball—are arresting tributes to the Crescent City. But Blanchard’s music shines brightest when interweaved throughout Spike Lee’s incendiary joints like Malcolm X, 4 Little Girls and Miracle at St. Anna. Today, he’s brought his lyrical majesty to the stage, composing for hit Broadway plays The Motherf****r with the Hat and the all-Black revival of A Streetcar Named Desire, which, again, allows him to exploit his N’Awlins roots.

His treatment for George Lucas’s Red Tails only exclaimed the trademark of his legacy: his charts aren’t just sweeping soundtracks that help tell stories, but highlight the legacy of Black struggle of past and present times. As he prepared for the inaugural International Jazz Day, Blanchard shared his journey with us.

How much did the music of New Orleans affect you as a child?

It had an enormous effect. It’s the reason why I’m playing music. At my elementary school, there was a local musician named Alvin Alcorn, who came to the school. We had a very progressive principal. She always brought dance troupes, art exhibits, music performances—classical and jazz. Alvin Alcorn was a trumpet player and he came by to give this demonstration about what New Orleans music was all about and I remember hearing him. I kept thinking to myself, “That I want to do.” The sound of that music was embedded into my psyche; the very spark to my interest of playing jazz.

What was it about Alvin Alcorn’s playing that attracted you?

When I heard him, I was in 4th grade, elementary school. I had been taking piano lessons since I was five years old, and when I heard him, he played with vibrato. He could bend notes. The trumpet had more of a vocal-like quality than the piano did and I kept thinking, “I can’t do that on a piano [laughs].” So he was just very lyrical, with a vocal playing style that really got my attention.

Did the piano lessons help you to pick up the trumpet faster?

Did the piano lessons help you to pick up the trumpet faster?

Oh, yeah. To this day, I tell any person who wants to play music that one of the things you should always do is learn the piano, because that’s where it all comes from. Roger Dickerson, my [high school] composition teacher, one of the things he taught me is that if it works on piano, it’ll work anywhere. For example, I had a teacher by the name of Louise Winchester who taught me theory around the age of 12. Just that little bit of theory and piano knowledge taught me a great deal about deciphering tunes that I’d hear on the radio, picking out harmonies that I’d heard in certain performances. It helped me understand how to break down and analyze music. So, I think it’s essential for anybody who wants to be an artist to learn piano because that’ll help you to understand how music is constructed.

Does it matter whether or not you learn piano before or after another instrument?

No, it doesn’t matter. It’s all about what piques your interest. And then from that point on, you start to branch out. It’s the same concept for learning jazz in general. We don’t always come into jazz at the beginning of its history. When I got into jazz, I got into it from the music I heard in the 70s. Then I had to go back and study the history after that. The same thing can apply when learning an instrument.

Jazz of the 1970s got you to go farther into its history. Could you elaborate on that?

For me, I wanted to know as much as I could about playing the trumpet. The first person I got into was Maynard Ferguson because that’s what I was hearing at the time. Then as I got older, I went back and I listened to Miles Davis, Clifford Brown. Those were the two guys who really, really got me into it. Then it spun off from there to Louis Armstrong, Woody Shaw, Clark Terry. That’s when I got more and more interested in the trumpet, after I got interested in what these guys were doing. Once you listen to Clifford Brown, you can see he comes from Fats Navarro a little bit, which takes you back to Roy Eldridge. That all comes from that passion in learning anything you can about topics.

As a teenager, you listened to all these jazz giants to learn history. What did you listen to for fun?

[Chuckles]. Jazz. During the late 70s, early 80s, I was so serious about jazz I didn’t listen to anything else. So there’s a whole period of that pop culture that I don’t really have a relationship with. But when I was coming along, I still listened to Parliament Funkadelic, Mandrill, Mother’s Finest, Earth, Wind and Fire, Kool and the Gang . . . stuff like that. A little bit of Jimi Hendrix. And then, of course, I was listening to classical music because of my father. My father loved opera, so there was a lot of opera being played in the house.

You and fellow New Orleans trumpeter Wynton Marsalis came up together. How instrumental was your relationship with him?

You and fellow New Orleans trumpeter Wynton Marsalis came up together. How instrumental was your relationship with him?

It was my relationship with all of those [New Orleans musicians]: Wynton, Branford, Donald Harrison, Claude Montegue, Julian Castillo, Tony Dylan. Our relationship was crucial because we were the only ones we knew that had an interest in this music. We came from all over the city, and we would always find each other at summer music camps or jazz workshops. Those relationships that we developed helped us stay on track because we knew even though we went to music schools, there weren’t that many kids interested in jazz. So moving forward, we were all happy when Wynton got the gig with Art Blakey. It was like we all got the gig with Art Blakey. Those relationships are still important to this day. I see the things that Wynton is doing, that Branford is doing, Donald Harrison, Harry Connick Jr. They’re still inspiring me today.

I remember Harrick Connick Jr. talking about a musicians’ village after Katrina. Are you saying that there was a sub-community amongst New Orleans musicians when you were younger?

TB: Definitely, man. We all went to the same high school, New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts, NOCCA for short. That was the first time that I was excited about going to school everyday. When I got to school, I felt like I was at home. I was around like-minded people, learning something new everyday. I’ll never forget that. I actually remember being sick and told my mom I was still going to school and she tried to get me to stay home. I said, “No, no, no! I have to go to school,” because I knew we were going to do something in school that day that I didn’t want to miss out on. I was around other people who were just like me.

You mentioned when Wynton got the gig with Blakey, you felt like you got it, too. Well, eventually you did get that gig. Tell me about getting word that you were in the Jazz Messengers.

We were at Fat Tuesday. It was a jazz club and we all went there to sit in with the band; we didn’t realize it was kind of like an audition. Next thing you know, the road manager John Ramsey comes out and says, “O.K., next week, we’re going to Chicago, and after that we’ll be in Europe for 10 weeks,” and I was like, “Excuse me?” He said, “Welcome to the Jazz Messengers,” and I went “Wow!” I was overjoyed. To think that I was going to be in Europe for 10 weeks with Art Blakey was unfathomable.

Many jazz artists who’ve gone to school to study music have said playing with legends is just as heavy an educational experience. Did this apply to you while playing with Blakey?

Oh, yeah! I was 19 years old when I joined that band. Prior to that, the only thing I really had were the local musicians that I played with in New Orleans and records that I studied. Studying the records was a great help, but actually playing with one of the legends was something you cannot measure. I remember once I joined this band, I had to go back and listen to all my records again because I had a new perspective. And also, by being 19, I was growing up as a young man; so there were a lot of things that I was going to do culturally and socially at that time as well. I always tell people that I was in that band for four years, but I felt like I’d aged by 40 because of all my experiences.

Much of your success came in the 1990s when you were collaborating with Spike Lee. How did this relationship start?

It all started with a man named Hal Vick, a jazz saxophonist who was friends with Spike’s dad. They wanted to put together a band of young musicians to play on the earlier scores. My name was one of the few that came up to be a part of that. I think we were doing School Daze. The Lakers had just won one of their championships. I walked into the session with a Laker hat on, Laker t-shirt, purple and gold Converses. Spike looked me up and down and said, “Oh, you’re a Lakers fan, huh?” That began our relationship. He kind of remembered me from that, but it wasn’t until we were doing Mo Better Blues that he heard me on piano and asked me to use what I was working out on piano for Mo Better Blues.

It all started with a man named Hal Vick, a jazz saxophonist who was friends with Spike’s dad. They wanted to put together a band of young musicians to play on the earlier scores. My name was one of the few that came up to be a part of that. I think we were doing School Daze. The Lakers had just won one of their championships. I walked into the session with a Laker hat on, Laker t-shirt, purple and gold Converses. Spike looked me up and down and said, “Oh, you’re a Lakers fan, huh?” That began our relationship. He kind of remembered me from that, but it wasn’t until we were doing Mo Better Blues that he heard me on piano and asked me to use what I was working out on piano for Mo Better Blues.

What was your reaction when Spike asked you to compose the score for Jungle Fever?

I called Roger Dickerson, my [high school] composition teacher, and he said, “Listen, man, trust your training. Just go in there and do your thing. Trust your training.” O.K., cool! So when [Spike] called me to do Jungle Fever, one of the things that I know, just because of what I saw in the studio when I was working on the earliest stuff was that you didn’t have time to mess around and experiment like when you do when you’re making records. So, my first thought was, “Man, I better be organized.” So I did a lot of homework in terms of listening to different scores, checking out some physical scores, and getting as prepared as possible for what it was going to be. It was a big learning experience.

How did you handle the transition of going from Jungle Fever to Malcolm X?

It was an extremely scary thing because it was the second film I ever scored in my life! One of the things that was unnerving about it was it was Malcolm X, and everybody had their own opinion about Malcolm X. A lot of people knew I was working on it with Spike. Everywhere I went people would say the movie better have this, you should have this. I knew what I had to do was I had to go back and think about my own relationship with Malcolm X in terms of how I learned about him, what it was I felt when I heard about him. I remember a musician from Detroit named Willy Metcalf. He used to have these summer jazz camps, and we used to do these performances out in the park. I was 14 or 15 at the time. We were taking a break and he put on a Malcolm X [speech] record where Malcolm was taking about how revolution is bloody. Man, I remember being terrified. I was like, “Who is this guy?” Everybody else out in the park who heard was cheering. That led me to learn more about him. That’s the reason, when you listen to the opening of the film, that’s the reason for the big, long crash, because it was a shock to my system, and the pulsating drum thing was my heartbeat. The solo melody was because in that public place I was having a solitary experience.

In 2006, you scored Spike’s Katrina documentary When the Levees Broke, in which you appeared as well. How different was it to compose music about something that happened to you rather than something that was fiction?

It was extremely tough, extremely tough. I came back to do it here in New Orleans, and it was just very bizarre writing music in my home and needing to get away from the subject but couldn’t because you step outside right into the very thing I was dealing with inside. I really had to keep my mind on track because I really appreciated everything that Spike was doing. After the hurricane . . . I have an apartment in L.A., so I took my family there for six months. While we were there, Spike was doing the Inside Man and said “I’m ready to do this, but I’m going to come to you.” He came to the apartment and the first thing he said was, “Hey, man, I’m going to do a story on those levees because those people need to tell their story” before he even said hi. When he did that, my respect for him went sky high. I thought it was a brilliant piece of documenting a moment in time in our history.

Your latest film score was 2011’s Red Tails. What was it like dealing with George Lucas compared to Spike Lee?

Your latest film score was 2011’s Red Tails. What was it like dealing with George Lucas compared to Spike Lee?

It wasn’t much different, actually. One of the things that I realized when working with them is they’re the type of directors who are comfortable in their own skin. They’re comfortable in terms of what they know, and they’re comfortable in hiring competent people and entrusting the film to those folks. George, just like Spike, once we came up with a lot of material and dramatic ideas, he told me, “Go have fun.” When we got to the studio, he’d listen to cues, and had comments here and there. But he was very easy to work with. Anthony Hemingway was the director and the one who hired me. I tried to make sure I paid respect to Anthony and what he was looking for as well. We wanted to mix in the elements of African-American culture to help drive the pulsating portions of the score and not just have it be a typical war movie type of sound. I had a ball. I cried a lot working on that film, just as I had with Miracle at St. Anna and Malcolm X. One of the things I’m always about is people who give their lives up for public service and public injustice. These were highly intelligent men, young men in the prime of their lives, fighting in a war to prove not only to those folks but to our countrymen that they were worthy and that we were able-bodied people who had just as much right to fight for their country as anybody else.

Examining your catalog, the arc of your work deals mostly with Black social struggle. Is that something that you seek?

Part of being an artist is dealing with social issues of your time. Those are the things that move me. Those are the things that make my heart vibrate. I can’t walk this planet and not deal with them in some regard; I can’t exist and ignore those issues. My father studied opera, and a lot of his friends love operatic music. I look at those men as very unique, but at the same time, they came from a generation of folks who understood we were all a very diverse group of people and had varied interests in a lot of different things. My interest is to shine a light on that and also shine a light on a lot of the injustice of the world.

April 30th marks the first annual International Jazz Day. How will you be commemorating the festivities?

First of all, it’s an immense honor to have an International Jazz Day. When you think about it, there are not many events that we celebrate internationally simultaneously. To me this is a very big deal to have this event. It makes a statement about the power of this music; the power that it had and is still having in all communities around the world. It’ll inspire people all over the planet, meanwhile showing people that different views of different cultures can come together to make something extremely beautiful. I’m playing a couple things with Dianna Reeves and Herbie [Hancock], and I’m doing something else with Chaka Khan. It’s going to be a lot fun.

Check out iRock Jazz!