Matt Ventimiglia is a man who has hitched his wagon to a star, literally, from traveling the globe to see the eclipses in the best possible locations, as near as Baja, California, to remoter places like Australia and the high Arctic Ocean; a star gazer who shares with others his vast knowledge of the universe. When talking with Matt, it is difficult to spend less than an hour listening to his fascinating stories about the universe. He is an expert on film, an excellent photographer, and, what I believe to be, a true renaissance man in an age where the mediocre is more the norm than not.

Matt Ventimiglia is a man who has hitched his wagon to a star, literally, from traveling the globe to see the eclipses in the best possible locations, as near as Baja, California, to remoter places like Australia and the high Arctic Ocean; a star gazer who shares with others his vast knowledge of the universe. When talking with Matt, it is difficult to spend less than an hour listening to his fascinating stories about the universe. He is an expert on film, an excellent photographer, and, what I believe to be, a true renaissance man in an age where the mediocre is more the norm than not.

I met Matt Ventimiglia at the Griffith Observatory recently, one Saturday in January. He was behind the information desk answering one technically challenging question after another being thrown at him from my sister’s father-in-law, who used to work as chief engineer for a contractor of NASA during the early years of space travel. I was engaged in listening and adding a few volleys of my own while discovering that Matt had a keen interest in following eclipses throughout the world. He’s been to seven thus far, from Australia to Zambia. He’s worked at the Griffith Observatory since it reopened in 2006 and has known its current director, Edd Krupp, for 20 years. He understands the heavens and quotes poetry. He is a science fiction buff and has actually worked with the likes of Ray Bradbury for a thesis he’d written on “The Adaptations of Moby Dick,” and he met Leonard Nimoy as an extra in a documentary filmed at the Griffith Observatory and shown in its Leonard Nimoy Event Horizon Theater.

I was intrigued by Matt’s statement that we are all made of stardust and are all a part of this vast universe. We talked about the continuous present of Bruce Kawin, professor of literature and film studies at the University of Colorado in Boulder. [Check out his books at Amazon.com, especially Telling it Again and Again: Repetition in Literature and Film (1972)] and compared it to totality, the point when the sun is completely eclipsed by the moon or where the full moon can be eclipsed by the earth’s shadow, rendering the moon dark. (As seen from the moon, the sun is being eclipsed by the Earth . . . .) Totality is the point where it seems you are witnessing eternity.

I was intrigued by Matt’s statement that we are all made of stardust and are all a part of this vast universe. We talked about the continuous present of Bruce Kawin, professor of literature and film studies at the University of Colorado in Boulder. [Check out his books at Amazon.com, especially Telling it Again and Again: Repetition in Literature and Film (1972)] and compared it to totality, the point when the sun is completely eclipsed by the moon or where the full moon can be eclipsed by the earth’s shadow, rendering the moon dark. (As seen from the moon, the sun is being eclipsed by the Earth . . . .) Totality is the point where it seems you are witnessing eternity.

Matt is a graduate student studying paleontology at CSUN (California State University Northridge) and is very busy. I was very fortunate that he found the time to speak with me about his travels, astronomy, literature, film, and the Observatory. What follows is our dialogue.

Northridge) and is very busy. I was very fortunate that he found the time to speak with me about his travels, astronomy, literature, film, and the Observatory. What follows is our dialogue.

************

How long have you worked at the Griffith Observatory? What are your most memorable moments?

I’ve worked there for about three years although I’ve patronized the place ever since moving to Southern California in 1979 and have known its current director, Dr. Ed Krupp, for nearly 20 years. Most memorable moments include watching the last transit of Mercury (Nov 8, 2006), seeing Comet McNaught (Jan/Feb 2007, visible in broad daylight through binoculars), and lecturing to the public in the Leonard Nimoy Event Horizon Theater. I met Leonard  Nimoy while appearing behind him as an extra in the documentary film we show in his namesake theater. Finally, I always enjoy it when succeeding to explain in simple terms a scientific concept or natural fact a patron was previously unaware of. You can always tell when you’ve achieved success by the way they offer sincere thanks. This is very satisfying.

Nimoy while appearing behind him as an extra in the documentary film we show in his namesake theater. Finally, I always enjoy it when succeeding to explain in simple terms a scientific concept or natural fact a patron was previously unaware of. You can always tell when you’ve achieved success by the way they offer sincere thanks. This is very satisfying.

What are you doing there now, and what are your future plans and adventures? And you also referenced Carl Sagan for one of the shows.

I recently filled in for a few of the “Let’s Make a Comet” presentations in the LNEH theater when the “trained” presenters couldn’t attend. But these programs are now being presented only for school groups on weekday mornings, so I won’t be doing it again until possibly Spring Break or summer when regular public “holiday” programming resumes.

I only wish Carl Sagan were alive to see what a monster he’s created . . . ME! I spoke with him several times over the years before he died, but I don’t think he would have remembered me among the throngs of his admirers.

I work Observatory weekends for the remainder of this month but will limit my time to Fridays or Sundays only during the spring semester.

I understand you follow eclipses worldwide. Tell me about your first eclipse in 1991.

I had no idea what to expect other than the photos I’d seen. It was a long one, nearly 7 minutes of totality, seen from a cruise ship between Baja and mainland Mexico. I was not planning to photograph the eclipse, just watch it with a spotting scope, but then realizing I would have plenty of time, I attached a camera and captured a pretty good shot at 400mm. It was a surreal experience watching the eclipse next to John Astin (Gomez Addams on the TV show “The Addams Family”), whom I’d met on the cruise!

I had no idea what to expect other than the photos I’d seen. It was a long one, nearly 7 minutes of totality, seen from a cruise ship between Baja and mainland Mexico. I was not planning to photograph the eclipse, just watch it with a spotting scope, but then realizing I would have plenty of time, I attached a camera and captured a pretty good shot at 400mm. It was a surreal experience watching the eclipse next to John Astin (Gomez Addams on the TV show “The Addams Family”), whom I’d met on the cruise!

What brings you back again and again?

The glory of it all . . . !

Why is it so addictive?

There’s no describing it in words, but when you see your first, you’ll understand . . . !

Totality sounds so romantic, like the point in time where everything stops. Explain “totality” and what your experience is at totality.

I remember one elderly Englishman in a documentary called “The Great Eclipse,” by far the best documentary on eclipse watching, the “Woodstock” of eclipse films . . . secondhand VHS tapes may still be available . . . check Amazon.com, who described it as feeling like he was about to die. You could do nothing to stop it, but time itself seemed to freeze . . . .

VHS tapes may still be available . . . check Amazon.com, who described it as feeling like he was about to die. You could do nothing to stop it, but time itself seemed to freeze . . . .

I know this is not what totality means, but I think I’ll change the meaning a bit for a poem or song.

You’re not far off the mark. Also, a tradition for lovers has developed: to “pop the question” following totality, during the exit diamond ring, especially if the guy doesn’t yet have the ring to produce. The eclipse diamond ring becomes the proxy . . . .

Would you consider shooting a documentary about one of your eclipse cruises?

Although I am somewhat of a trained filmmaker, I actually prefer still photography because of its ability to freeze and preserve moments of time.

During our discussion at the Observatory, you quoted a verse to me by Walt Whitman about a blade of grass being made of stardust and compared it to people being made of stardust. Could you expand on that?

The quote is from “Leaves of Grass”: “I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journeywork of the stars.” But Whitman didn’t mean that grass was made of stardust. He just meant that grass was as interesting to him as stars. I’d agree on some level, but I also think we are actually made of stardust, born from the Big Bang and nuclear reactions within stars, the heavier elements coming from supernova . . . . Whitman also wrote a poem called “I Heard the Learned Astronomer,” where he disparages science and scientists. The caricature of his astronomer is a guy too obsessed with numbers and seemingly oblivious to the beauty of the universe. I can forgive Whitman for that, though. He just met the wrong astronomer, and first impressions are always blinding . . . .

I understand that you are studying paleontology. That seems very different from astronomy. What draws you to that field of study?

Both subjects are similar in that they involve processes spanning extreme passages of time, but also because they both try to ask the most mysterious questions: How did life come about and develop into what it is today, and is there life elsewhere in the universe?

You mentioned your interest in math. What specifically do you love and dislike?

I like the way it models how the mind works; its attempt to order things with symmetry and logic and the joy you get learning something new through derivation or visualizing geometrical relationships. I don’t like long, tedious calculations with long, tedious numbers . . . .

Tell me a little about your first thesis, “Adaptations of Moby Dick” from your degree in cinema history and criticism, 1984.

I wrote it while consulting with author Ray Bradbury, who wrote the screenplay for the 1956 John Huston film starring Gregory Peck. Bradbury is still a close acquaintance. In fact, I’ll be calling him at noon today. Looking back on it now, the thesis is rather wordy and immature. Yet because it was apparently the first thesis to cover the topic of film, theatrical, musical, comic book and illustrated adaptations, it was mentioned by Prof. Elizabeth Schultz (University of Kansas) in her book Unpainted to the Last: Moby Dick and 20th Century American Art.

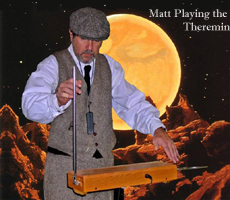

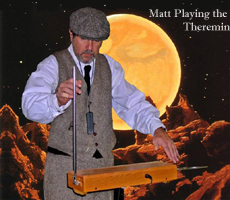

You mentioned your love of a very unique instrument you play, called the  Theremin, and that i t is in two theatrical films that you know of,The Delicate Delinquent, starring Jerry Lewis, and a foreign film (Argentine) La Nina Santa (The Holy Girl), where a street musician plays the Theremin. What do you love about the instrument, and would you be willing to record a song or two?

Theremin, and that i t is in two theatrical films that you know of,The Delicate Delinquent, starring Jerry Lewis, and a foreign film (Argentine) La Nina Santa (The Holy Girl), where a street musician plays the Theremin. What do you love about the instrument, and would you be willing to record a song or two?

There are also documentaries such as “Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey.” What I love about it is the tonal quality, like a violin with one string, using vibrato to emulate the human voice. I also have fond memories of its use in 50s science fiction film soundtracks, although this is considered rather vulgar by some , but the Theremin is no longer used as a serious concert instrument; so why not celebrate its place in popular culture?

this is considered rather vulgar by some , but the Theremin is no longer used as a serious concert instrument; so why not celebrate its place in popular culture?

Yes, I would love to record . . . when I can find the time to practice . . . ! I’m a bit rusty right now.

When we spoke at the Observatory, we talked about the eternal now. You quoted from the movie, The Thin red line. Could you expand on that?

The monologue from The Thin Red Line that most relates to this question is when Pvt. Witt describes watching his mother die and how she seemed to accept it calmly. Witt mentions never seeing any sign of “immortality” in his daily experience, but hoped he could face his own death with the same “calm, because that’s where it is, the immortality I hadn’t seen . . . .”

I don’t really know how one can apply the concept of “continuous present” (see critical writings of Bruce Kawin) to my philosophy of life other than to savor pleasant moments and measure them unflinchingly next to the unpleasant.

Where have you traveled to see the eclipses?

1991 Cruise ship Viking Serenade off Baja between mainland Baja and the Gulf of California

1996 The one I took my parents to, seen north of the Galapagos Islands aboard the tour boat Corinthian

2001 in Zambia near Lusaka (the capital)

2002 in Australia in the southern Outback

2005 North of Pitcairn Island on the cruise ship Paul Gauguin

2006 North Africa in Libya, south of Tobruk

2008 in the high Arctic Ocean

Where will you see your next eclipse?

My next eclipse trip will be in July, a cruise from China to the eclipse maximum southeast of Japan. The tour will begin in Beijing at the Great Wall.

Tell me about your most memorable eclipse moment.

The most interesting one seen from northern Iceland in 2003 on the last day of May, rising before annularity, appearing like a neon hula hoop, partially obscured by clouds. I loved the coincidence of seeing the annular solar eclipse (a solar eclipse in which the moon covers all but a bright ring of the sun around the circumference of the moon) from Iceland on the same day as in the movie, Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959), on the “calends of June” (The last day of a month is called the “calends” of the next month; for example, the 31st of June is the calends of July) that the expedition enters the earth from inside the caldera of Snæfellsjökul, a name which refers both to the icecap on top and the summit of the volcano. The film version altered the novel’s calends of July (the 31st of June) to June, the 31st of May. I just loved the coincidence of seeing the annular solar eclipse from Iceland on the same day . . . .

Annular eclipses seem to be very special. How many have you seen?

I have seen a total of four annular eclipses, two on the Pacific coast (California and Mexico), one in New Mexico, and one in Iceland.

*****************

“Descend, bold traveler, into the crater of Snæfellsjökull, which the shadow of Scartaris touches before the calends of July, and you will attain the centre of the earth; which I have done.”

– Arne Saknussemm of

Journey to the Center of the Earth, Jules Verne, 1864

After spending time with Matt Ventimiglia, I believe I just ascended from the depths of the earth to encounter a taste of the heavens. And you can read his article about his last eclipse adventure in “Griffith Observer,” a monthly issue put out by Griffith Observatory. Details at http://www.griffithobs.org/

*Note: Matt Ventimiglia works as a tour guide for Griffith Observatory, however he is not an official representative.

See the image gallery related to this interview

Interviewed by Lisa Trimarchi

Welcome to a new year full of prosperity coupled with wonderful new levels of health, dear ladies of Agenda. We address the age-old question of why we cursed men hold this unfair advantage in the battle of the bulge and further yet, how to help you reap said benefits. The truth of the matter is that men do have major weight-loss advantages over you lovely ladies, combined with disadvantages as a woman. Fret not though, as there is always a way. The first male advantage involves body composition, enabling men to burn calories at an accelerated rate in comparison to women. Specifically, I am referring to greater amounts of muscle mass, extremely efficient fat burning marvels. Every extra 1 lb of lean muscle devours an extra 50 calories a day by simply existing. Might not sound like much, but should you add an extra 5 lbs of lean muscle mass to your body (which visually is one toner leg), you would burn an extra 500 calories a day. In one week’s time you will have burned 3500 calories, 1 lb of fat, simply due to you having one gorgeously toned leg. (I recommend you tone both together though. Might look odd if you don’t.) This either means you can eat an extra sandwich with 2 pieces of fruit, staying exactly the same size or change no eating habits and naturally lose nearly 1 lb a week. Not bad.

Welcome to a new year full of prosperity coupled with wonderful new levels of health, dear ladies of Agenda. We address the age-old question of why we cursed men hold this unfair advantage in the battle of the bulge and further yet, how to help you reap said benefits. The truth of the matter is that men do have major weight-loss advantages over you lovely ladies, combined with disadvantages as a woman. Fret not though, as there is always a way. The first male advantage involves body composition, enabling men to burn calories at an accelerated rate in comparison to women. Specifically, I am referring to greater amounts of muscle mass, extremely efficient fat burning marvels. Every extra 1 lb of lean muscle devours an extra 50 calories a day by simply existing. Might not sound like much, but should you add an extra 5 lbs of lean muscle mass to your body (which visually is one toner leg), you would burn an extra 500 calories a day. In one week’s time you will have burned 3500 calories, 1 lb of fat, simply due to you having one gorgeously toned leg. (I recommend you tone both together though. Might look odd if you don’t.) This either means you can eat an extra sandwich with 2 pieces of fruit, staying exactly the same size or change no eating habits and naturally lose nearly 1 lb a week. Not bad.